Ramat Rahel was first settled in the days of the Judaic monarchy during the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. It was then

alternately settled during the Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and early Islamic periods, after which it remained

unpopulated for approximately a thousand years. It was resettled in 1930 by Jewish pioneers who planted the groves of shady

pine trees that give the modern site its distinctive character.

History of Excavations

1930–31

Ramat Rahel was first excavated in 1930–31 by Benjamin Mazar and Moshe Stekelis, under the auspices of the Israel

Exploration Society. These were limited rescue excavations. Some two hundred meters to the south of the hilltop they found

a Jewish burial cave. Stray sherds collected during the excavation, such as lmlk seal impressions, were

the first indication of the importance of Ramat Rahel in early periods. The burial cave was published by the excavators

in a number of articles.

|

The Burial Cave excavated by Benjamin Mazar and Moshe Stekelis serves today as a memorial to Ethiopians who died while immigrating to Israel |

1954–1962

In 1954, in conjunction with the kibbutz's plans to construct a water tower at the summit of the site, Yohanan Aharoni

conducted a salvage excavation sponsored by the Israel Department of Antiquities (later the Israel Antiquities Authority).

He unearthed a segment of casemate wall from a palace that dated to the Judean Monarchy period along with a rich collection

of stamped jar handles from the Judean Monarchy and the post-exilic Persian periods. Following the salvage excavation, which yielded

significant finds, Aharoni returned to the site between 1959 and 1962 for four additional seasons, sponsored by the

Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Institute of Semitic Studies of the University of Rome. His findings were published in

both preliminary form and in a two-volume final excavation report.

|

| Aharoni's plan of the architectural remains |

1984

Gaby Barkay excavated at the site in 1984 on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, the Israel Exploration Society,

the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums and the American Institute of Holy Land Studies on Mount Zion. He concentrated on

soundings both in and outside the palace as well as under the Byzantine period church. The results of these excavations have not as of

yet been published, but an editorial note in the NEAEHL (s.v. Ramat Rahel) summarizes his conclusions.

1999

In the framework of the site's restoration and reconstruction as an Archaeological Park, trial excavations

were conducted by G. Suleimanny on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. Only a few squares were opened and results

have not as yet been published.

2004–2010

The renewed excavations at Ramat Rahel

Since 2004 renewed excavations at Ramat Rahel are conducted by Tel Aviv University (Israel) and Heidelberg Universität (Germany).

Four excavation seasons were already performed in 2005–2008. For details and results of the last three seasons see

Tel Aviv University and Heidelberg Universität Project. The next season will be conducted during 2009 summer.

For details about the next season and to join the dig see Call for Volunteers.

|

| Ramat Rahel Archaeological Park after reconstruction work by Ran Morin |

Past Excavations Results

As at other hilly archaeological sites, differentiating between strata at Ramat Rahel has been quite difficult. The majority of

remains were found at a depth of less than 1.5 m, most building materials were reused, and the lime furnaces of later

periods caused the destruction and disappearance of many of the earlier remains. The generally accepted view,

however, is that there are five main strata at the site:

Stratum Vb—The First Settlers: Royal Enterprise or Village Dwellers

|

| lmlk seal impression on jar handle from Stratum Vb, dating it to pre-701 BCE |

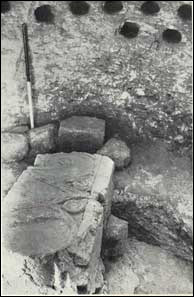

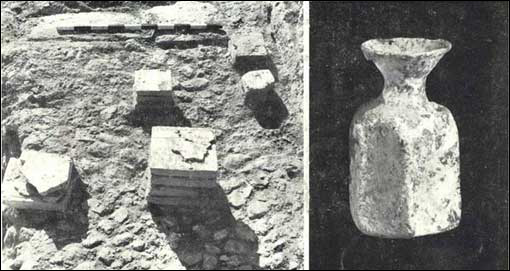

Scanty architectural remains from the end of the 8th and early 7th centuries BCE were discovered. The most important architectural

find from this stratum is a small section of a casemate wall composed of hewn stones thought to have been part of a small citadel or

a palace. The stones are identical to those of the Stratum Va citadel. The existence of this stratum is clear from the many 8th-century

or early 7th-century-BCE pottery vessel types, together with 145 lmlk seal impressions, private seal impressions and an ostracon.

Most of this material was found in occupational layers under the Stratum Va citadel.

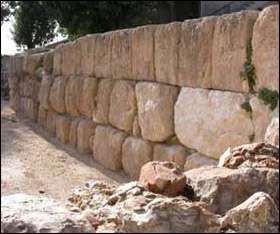

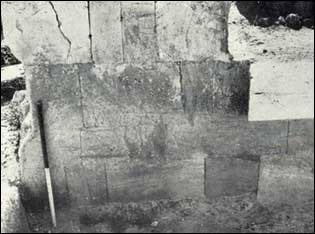

Stratum Va

Stratum Va spanned from the end of the 7th to the beginning of the 6th century BCE and included a much larger and better-constructed

royal citadel. It had an outer fortification system and an inner citadel with a palace. The outer fortification system was composed of a

massive, 3–4-m-wide wall. Though only small portions of it have been exposed, it may be assumed that it enclosed an area of some five

acres (20 dunams) on the top of the hill. Inside this wall, no building remains were found. The inner citadel, measuring 75 x 50 m, stood

at the northeastern corner of the courtyard. It was surrounded by a 5-m-wide casemate wall. The rooms in the wall had floors covered

with a thick, hard plaster, suggesting that they were storerooms.

|

|

|

| Dressed stones from walls of the Stratum Va palace |

The gate to the inner citadel was in the centre of the eastern wall and was reinforced with buttresses. It had two cells, one on each

side of the entrance, with floors of massive stone flags. The gate was closed with inner and outer double doors. A narrower opening

into the inner citadel was located in the same wall, several meters to the south. The area inside the citadel was divided into a

stone-paved courtyard with buildings along the northern and western sides. The northern building consisted of an open inner

courtyard surrounded by several rooms, and it probably served as the king's residence. A narrow, hidden postern built of large stones

under the northern wall connected the citadel with the outside providing an escape passage.

The royal citadel at Ramat Rahel is one of the most instructive examples of Israelite-Phoenician architecture in the biblical period. The

construction of the casemate walls and the buildings of the citadel were of excellent quality, with smoothed and squared stones laid in

well-fitted courses. The main gate, built of large, dressed stones, also shows fine workmanship. Several complete proto-Aeolic capitals

were found in the ruins of the citadel; they once decorated the doorposts of the main gate and the entrances to the buildings.

Window balustrades consisting of a row of stone colonnettes, decorated with palmettes and topped with joined capitals in the

proto-Aeolic style, were also found. They probably adorned the upper story of the buildings inside the citadel. These decorative architectural

elements echo a verse in the book of Jeremiah, which describes the windows in the house of Jehoiakim, king of Judah: "and cut out

windows for it, paneling it with cedar, and painting it with vermilion... " (Jeremiah 22:14).

A luxurious Assyrian palace was found in the debris that covered the citadel after its destruction by the Babylonians. One of the unique

finds was a seal impression with the inscription to Eliaqim, steward of Yochin. Eliaqim is thought to have been an official of King Jehoiachin, king

of Judah and son of King Jehoiakim.

Stratum IVb

This stratum is highly puzzling: While no architectural unit could be ascribed to it, a large collection of small finds dating to

the Persian and Hasmonean periods were found. Almost all of them were retrieved from secondary context and their original location

remains a mystery. Hundreds of seal impressions on jar handles date to the Persian period. The site must have served as the main

centre of the Yehud seal impressions of all types, as nearly two hundred impressions were found. The many seal impressions on jar handles with

the name yršlm (Jerusalem) that were found at the site belong to the Hasmonean occupation. Unfortunately, in this

case, too, we do not have the architectural context within which these finds functioned.

Stratum IVa

Stratum IVa consists of a small Early Roman period village that dates from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE. After its destruction

in ca. 70 CE the site was abandoned until the 3rd century CE.

|

Columbarium cave used for raising pigeons. Note the Proto-Aeolic capital of the Iron Age palace in secondary use.

|

Stratum III

After a long period of abandonment, Ramat Rahel was resettled, this time by the Roman 10th Legion that was stationed in Jerusalem.

This settlement is dated to the 3rd and 4th centuries CE. In the western section of the site a typical Roman villa was erected. It

consisted of a peristyle court surrounded by rooms. Further to the east the Romans built an impressive bathhouse. Most of this structure was taken down

by Aharoni while excavating below to the earlier Iron Age remains. It included rooms with mosaic floors, pools of various shapes and a hypocaust. Clay

pipes and stone channels connected the different chambers of the bathhouse.

|

Paved courtyard inside Roman villa |

All these structures were still in use at the beginning of the Byzantine period and, therefore, the original floors were not preserved.

|

| Remains of Roman bathhouse excavated by Aharoni |

Stratum II (a & b)

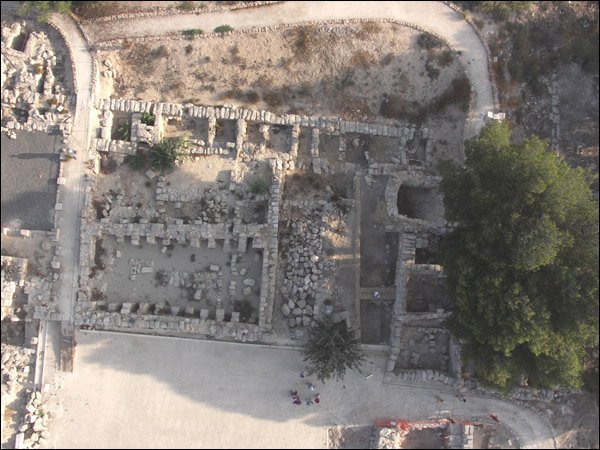

Remains dating to the Byzantine period were found in all parts of the site and it seems that during this period Ramat Rahel reached

one of its peaks. Aharoni reported on finding two phases of a large Byzantine period monastery and a church, surrounded by a

village (mid-5th and 6th centuries CE). The church is located in the northeastern part of the site. It is a basilica-like building with an

apse facing east. Mosaic floors with geometrical patterns decorated the floors. An alley to the south of the church separated the

church from a line of rooms belonging to a monastery. Until recently, the church was identified as the Church of the Kathisma, erected

by a wealthy matron, the Lady Ikelia, to commemorate the site where Mary rested on her way to Bethlehem. Excavations conducted to

the southwest of Ramat Rahel revealed an octagonal church. It is now believed that this is the true Church of the Kathysma, as it is

located right beside the road to Bethlehem. The relationship between the two churches is yet to be studied.

The monastery and the church were surrounded by many smaller buildings used as dwellings, storehouses, workshops and agricultural

installations. The villa and the bathhouse were also still in use during this period. Rock-cut tombs dating to the Byzantine period were

also recognized in many parts of the site.

Stratum I

This stratum consists of scanty remains from the early Islamic period (7th–8th Centuries CE) built upon the ruins of the Byzantine

stratum. The period is attested to mainly by the many coins found scattered on the surface.

|

| Ramat Rahel at the beginning of Aharoni's excavation. On the left is the young Prof. Moshe Kochavi |

The identification of ancient Ramat Rahel

Identifying biblical Ramat Rahel is still an open question. Three possibilities have been proposed:

Beit Hakerem (House of the Vineyard)

Aharoni claimed the site was the biblical Beit Hakerem (House of the Vineyard), one of the places from which flaming warning signals

were sent to Jerusalem at the end of the First Temple period (Jeremiah 6:1). The site was mentioned in the LXX supplement to Josh.

15: 59a as being near Bethlehem, and was also mentioned in Nehemiah 3: 14 as a centre of one of the districts in the province of

Yehud. Aharoni hypothesized that the site was built on one of the king's vineyards and that this is the source of the site's name.

Netofah

Mazar identified the site as Netofah, a site mentioned in 2 Sam. 23: 28; 1 Chr. 2: 54; et. al. (cf. Ez. 2: 22; Neh. 7: 26; 12: 28) as near

Bethlehem.

MMŠT

Barkay and others identified the site as MMŠT, which is mentioned on the lmlk stamp impressions. The names of

four local centres in Judah are mentioned on these impressions: Hebron, Sochoh, Ziph and MMŠT. The exact function of

these centres is highly disputed but they must have served the Judaic monarchy, perhaps for tax collecting and storage. The edifice

found at Ramat Rahel dates to the earlier part of the Iron Age and the large collection of lmlk stamp impressions led Barkai

to identify the place with one of the royal centres.

Whatever the ancient name of the site, during the Byzantine period, the town, as well as the church and the monastery located here,

was called Kathisma, after the holy well (Bir Kadysmu), where, according to Christian tradition, Mary rested on her journey to

Bethlehem.

|